Screenshot of Bay Cat story on LiveScience

Some of you may have read the Live Science article about the Bay Cat photo that was published last week. If not, you can check it out here. I am really excited that the photograph was published by a media outlet with such a large readership. It even made the front page of yahoo!! Even more importantly, I am ecstatic because the Bay Cat is getting more attention. As an endangered feline it needs all the help it can get.

I do want to elaborate on the article — they have word limits, I do not :). I wanted to discuss the tremendous importance of working with the biologists studying this wild cat to make a photograph of this incredibly elusive feline.

But first some background…

As always before an assignment, I read as much about the Bay Cat before I went into the field. The research allows me to put myself in a better position to either encounter the animal or place the camera traps in the right locations.

As soon as I started reading about this cat, I knew that getting a photograph of it was going to be tough. There was so little known about it. In fact, by 2004 only 12 specimens had ever been found, and direct sightings (known to the outside world) could be counted on one hand. Nothing, besides educated guesses, is known about their predation, social organization, reproduction, and development.

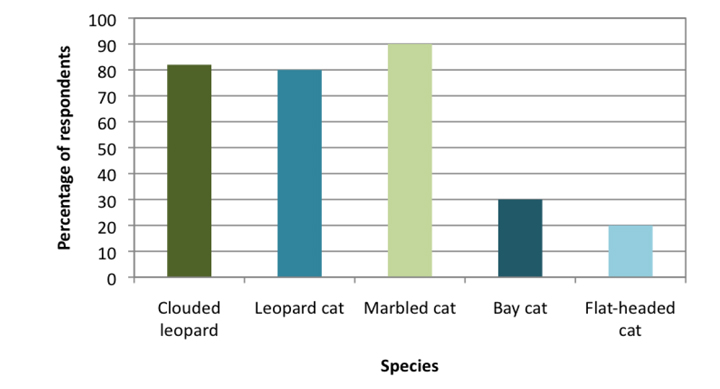

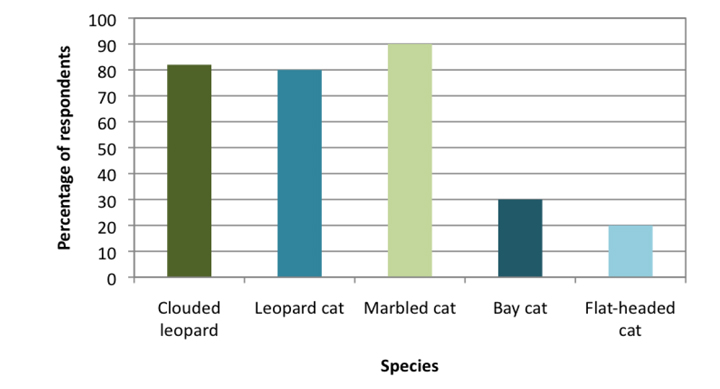

And this isn’t even the case just on a global level, but even on Borneo, which the Bay Cat is endemic to (only found there). Less than 30 percent of people that live in the rainforest who were interviewed in a study could identify the Bay Cat.

The percentage of people able to name the species of Borneo’s wild cat (Ross et al. 2010)

I left for Sabah, the most northern Malaysian state in Borneo, in February with high hopes and expectations (what can I say, being naive and optimistic is just the way I am). I would have five weeks to get the first ever high resolution picture of a wild Bay Cat. Luckily for me, I would not have to go at this endeavor alone, nor would I have ever had any chance of success without the help of Andrew Hearn and his team.

Andy is the expert on felids in Borneo. He knows everything there is to know about the five species of cats found on the island. In fact, most of the stuff I had read about the species was written by Andy. He has been doing his PhD research on the wild cats here for the last seven years and has seen all of them in person. Like I said, Andy is THE expert.

Bay Cat (Pardofelis badia) researcher Andrew Hearn checking camera trap, Kinabatangan River, Sabah, Borneo, Malaysia

Andy had gotten one or two pictures of the Bay Cat in some of his previous research sites, but none of the cats ever showed up at the same camera set twice. There seemed to be no predictable behavior for this animal. Not a good thing when you only have four digital SLR camera traps and a huge rainforest to put them in. Then, the luck seemed to change our way, at Andy’s latest research site he had gotten four pictures of the same cat at the same camera location. We knew where we had to place our cameras.

Two of them went right along the cats travel path, another 60 feet down the trail and another near a nice buttress root — I figured we may as well go for a pretty picture 🙂

After three weeks we checked the cameras. Besides finding the cameras covered with mold (due to the extreme humidity) there were no cats on the cameras. A very disappointing start, but at least we had gotten a few pictures of the Malay Civet (Viverra tangalunga).

Malayan Civet (Viverra tangalunga) in lowland rainforest at night, Tawau Hills Park, Sabah, Borneo, Malaysia

My confidence diminished, my optimism grew slim. A nice punch in the face came when Andy pulled the pictures of this research cameras, next to my SLR camera traps, showing how the Bay Cat had used a different trail this time walking right by my set-up, but also avoiding the camera further down the trail.

I could hear myself saying “If it was easy, everyone would be doing it”. This wasn’t the time to give up. We had the cameras in great locations, we just had to hope the cat would return before I had to leave.

Five weeks had almost passed and I was leaving in a few days. We hiked up the hill to check and pack up the cameras. Still, no Bay Cat, but at least we were able to get photographs of both the Marbled Cat and Sunda Clouded Leopard.

Marbled Cat (Pardofelis marmorata marmorata) in lowland rainforest, Tawau Hills Park, Sabah, Borneo, Malaysia

Bornean Clouded Leopard (Neofelis diardi borneensis) male in lowland rainforest at night, Tawau Hills Park, Sabah, Borneo, Malaysia

I returned home excited for having pictures of these species but also disappointed for not having gotten a picture of the Bay Cat. I felt like the ship had sailed on that opportunity. Little did I know that I would return to Borneo to work with Andy once again a few months later. Returning in November we once again placed the cameras in or near areas where Andy had gotten a Bay Cat photograph before using his research trail cameras. This had to be the time, it just had to.

Again things proved difficult. The rain was unrelenting making set-up quit difficult. “Just got to get on with it” is something Andy would always say when he encountered a difficult situation and I admire that about him, but it is also something I have tried taking to heart for myself. Even with the rains, difficult terrain, fire ants, leeches, horse flies, we just had to get on with it. Finally, after six days, all the cameras were in place.

Then, Andy and Gilmore Bolongon (Andy’s former research assistant and now a masters student) had to return to their principal research location on the Kinabatanagan River. I would meet up with them in ten days, right after doing the first camera check.

Arriving at the first camera after an exhausting first part of the hike I was hopeful, yet cautious. Scrolling through the pictures, reality struck, no Bay Cat picture.

Two more cameras await three more miles up the mountain. Not knowing what pictures await me up there is both a driving force, and a barrier. It would almost be easier not knowing if there was a Bay Cat picture, then knowing for sure that there were none. I am way too curious of a person not to know, so I kept hiking.

I arrived at the second camera, only feet from the third camera. Again, no Bay Cat picture.

The third camera didn’t hold much promise due to its proximity with the unsuccessful second camera trap. It was located on a very faint game trail off of the main trail. My hopes were low. The scream I let out once I saw what was on the camera must have scared all the animals away in a two mile radius. If that didn’t do it, the dance I did after that would have. I was exhilarated. As soon as I could, I let Andy and Gil know. This Bay Cat picture exists because of the teamwork between all three of us.

Bay Cat (Pardofelis badia) gray morph male in lowland rainforest, Tawau Hills Park, Sabah, Borneo, Malaysia

Andy has eighty camera set-ups in this research site (160 in total, but there are always two per site to get both sides of the animal). Without them we would have had no clue where a good spot would have been to get the high-resolution picture. Even more importantly, with all of Andy’s research there will finally be some light shed on the biology of the wild cats here.

His research is looking at population size, density, habitat preference, habitat use, and prey base. With this information, it will be possible to draw up a conservation plan to protect this endangered species, as well as the other felids on Borneo. You can read more about his incredibly important (and fascinating might I say!!!) research here: http://borneanwildcat.blogspot.com/

Panthera, the world’s leading cat conservation organization, is partially funding Andy’s research. By donating to them you are directly helping them implement steps into conserving our wild feline friends. If you have a chance visit their webpage.

References:

Hearn, A., Sanderson, J., Ross, J., Wilting, A. & Sunarto, S. 2008b. Pardofelis badia. In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.1. <www.iucnredlist.org>.

Ross et al 2010. Framework for Bornean wild cat action plan

Sunquist, M., Sunquist, F. 2002. Wild cats of the World, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 48–51