You read that correctly, pumas are better for our health! How can a wild animal like a mountain lion be better for our health? We have all heard about the web of life. All things are connected, and there is a natural balance within an ecosystem. Pumas show us how removing part of that system shifts that balance, creating a system that is harmful to people.

Web of Life

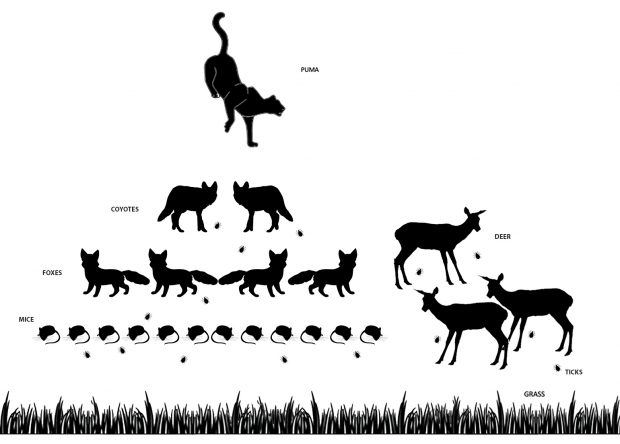

Let’s first look at the web of life that a puma lives in:

In this very simplified (though accurate) system, pumas play two roles as the top predator in the ecosystem. They feed primarily on deer, and they keep coyote numbers in check. One one hand, this leads to a normal sized deer population for the ecosystem. On the other it means that there are more foxes in the system, because there are less coyotes predating them. This leads to mouse numbers that are also at normal levels for the system. Ticks feed all the animals within the system.

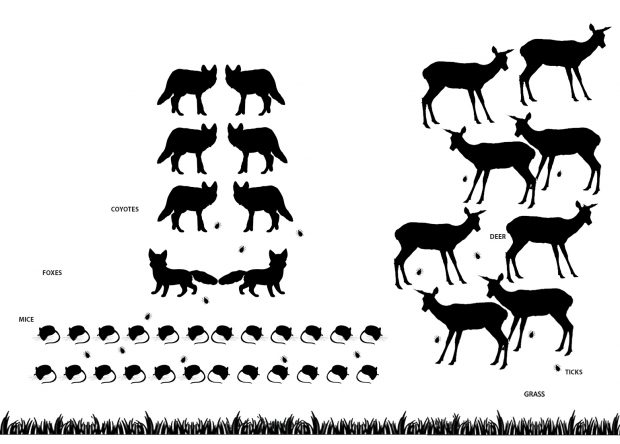

Now let’s compare the above system to that of the east coast of the United States, where pumas are no longer found.

Without the pumas, deer numbers have increased tremendously, causing vegetation to diminish due to overgrazing. More importantly, coyote numbers have increased, causing there to be fewer foxes, in turn leading a much higher number of deer mice. In this system there are a lot more deer for adult ticks to feed on and a lot more mice for larval ticks to feed on.

This is where the health aspect comes in. Ticks carry disease, including Lyme disease. Ticks get Lyme disease when they feed on mice, who are hosts to the disease causing bacteria. With more ticks present, there may not be a larger percentage of ticks that carry Lyme disease but there will be a larger number of individuals that are vectors of it. Due to the fact that cougars are not controlling deer or indirectly mouse numbers on the east coast, more Lyme disease carrying ticks are around, which leads to a higher rate of incidence for the disease in the area.

Tick and Lyme Maps

Let me illustrate the point with some maps.

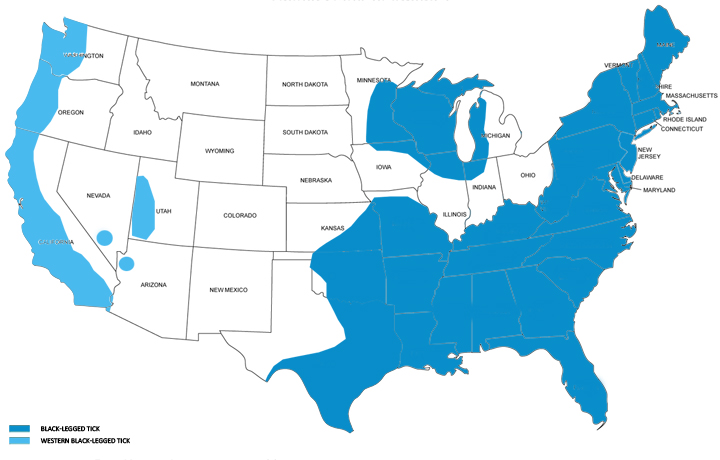

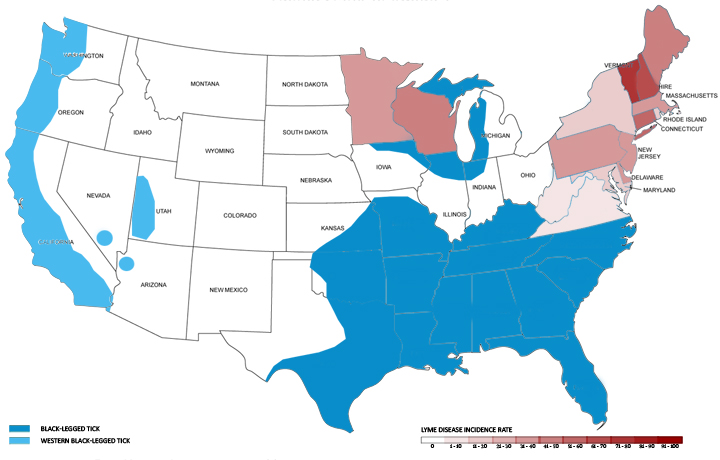

In the US, both the Black-legged Tick (Ixodes scapularis) and the Western Black-legged Tick (Ixodes pacificus) carry and transmit Lyme disease.

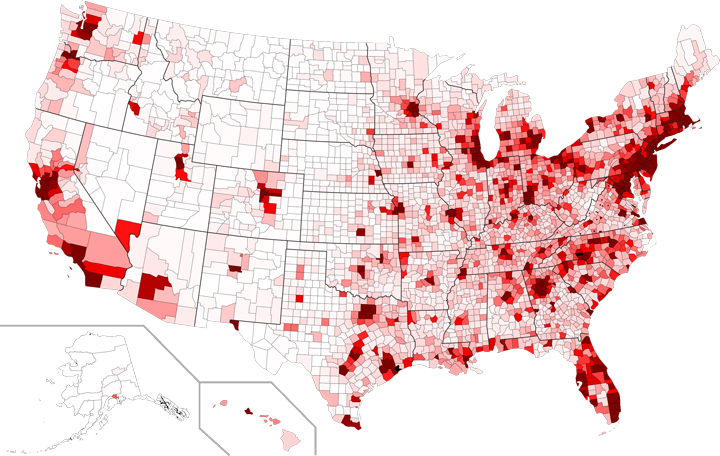

This is the area in which Lyme disease has the highest incidence rate (or, where it happens the most):

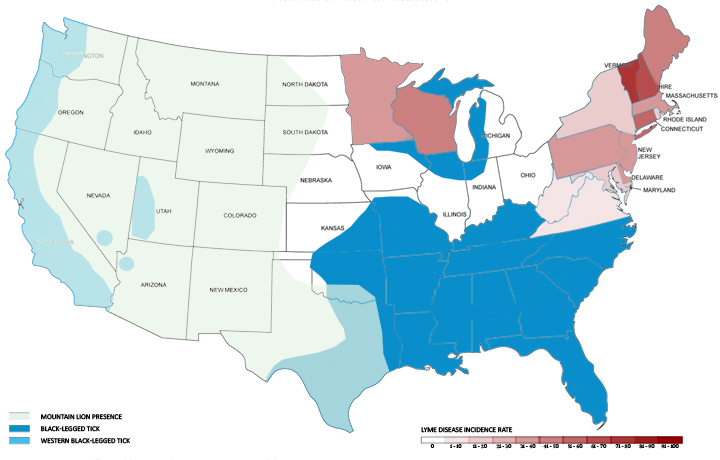

The fifteen states with the highest incidence rate of Lyme disease in the US (see Lyme Disease Association Analysis) — the darker the red the higher the number of incidences

As you can clearly see, the highest chance of infection is limited to the east Coast.

Now let’s look where Pumas currently live in accordance with the above data:

Even though Lyme disease and their vectors are present on the west coast of the US, mountain lions keep the tick numbers low (by keeping the deer and mouse numbers lower), therefore creating an overall healthier system for people. More mountain lions eventually means a lower chance of getting Lyme disease.

Is there space for pumas on the east coast?

Historically, cougars used to occupy the east coast where Lyme disease is so prevalent now, but they were extirpated from the region in the early 1900’s. Could a case be made for re-introducing cougars to the east coast? Now that they have been gone from the region for hundreds of years? Is there even space for them? Even though the western United States has greater areas of fully protected land, the eastern states still have plenty of habitat for pumas as well.

The population density map shows that cougars have no space left on the actual east coast. Nor would you want them to wander into New York City or Boston. Once you are more inland however, the population density is low enough where you can have successful co-existence between these cats and people. Having an re-introduction plan would help of course but even naturally, pumas are moving more and more east as time passes. Maybe sooner than later, Lyme disease will be less of an issue in the States, and all due to a wild cat.