Anytime before I go into the field I research the species I am intending to photograph intensively. Sometimes, the information available isn’t very extensive. This is often because the species is very elusive (which is also why I am sent in to photograph them using camera traps) or simply has not been studied much. This is the case for the Arabian Caracal, which was one of the species I was looking for when I went to Yemen. I mean, it doesn’t even have its own wikipedia page.

Therefor, to those looking for information on this amazing wild cat, I wanted to share the information I have found from different sources as well as my own personal observations about the Arabian Caracal.

Names

Arabian Caracal, Asian Caracal, Indian Caracal, Desert Lynx

Taxonomy

Latin Name: Caracal caracal schmitzi

The Arabian Caracal is one of the seven subspecies of Caracal (this simply means that it is a type of Caracal, and in theory it should be able to reproduce with any of the other subspecies of Caracal). Caracals belongs to the Caracal lineage and is therefor closely related to the Serval and African Golden Cat. Previously it had been placed in the Felis and Lynx genera, but molecular evidence has placed it in its own (monophyletic) genus.

Distribution

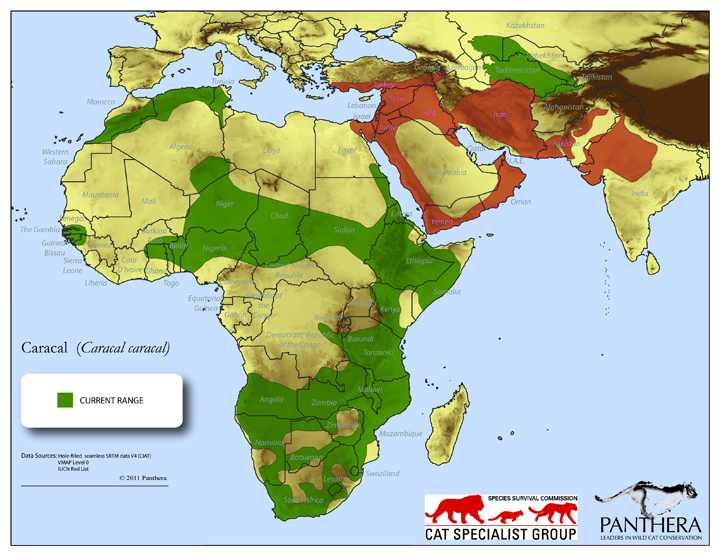

Overall Caracal range with the Arabian Caracal range denoted in red – Copyright Panthera and IUCN Cat Specialist Group

The Arabian Caracal is found in the Middle East as well as central and south west Asia. It’s range extends over the following countries: Afghanistan, Egypt, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

Description

The Arabian Caracal is a medium sized cat (though in broader terms it would fall into the small cat category). The Arabian Caracal subspecies is the smallest subspecies of Caracal. Its tawny brown fur with a white underside is lighter in coloration than the African subspecies. It has a slender body, with long legs. Its conspicuous features are its triangular ears, which have 4-5 cm long black hair tufts. Its tail is short relative to its body size and is about a third of its head and body length. It has hairs between its pads, to protect them when traveling over hot rocks or sand. The subspecies exhibits sexual dimorphism with males being larger than females.

Habitat

Shrubland, forest, and rocky outcrops are the perfect Arabian Caracal habitat – Hawf Protected Area, Yemen

Caracals are found in this habitat, but probably not in as high of densities – dried valleys (wadis), Hawf Protected Area, Yemen

The Arabian Caracal uses a variety of habitats but prefers drier woodland and semi-desert habitats. It requires some form of cover and is therefor associated with vegetated or rocky areas. It is not found in a true desert environment (this is also shown by the range map, as much of Saudi Arabia is a true desert).

Activity

The Arabian Caracal is solitary, and only comes together with a conspecific for breeding. It is mostly active at night, especially in areas affected by humans, but can also be day active. In winter, with lower average temperatures, it will be more active during the day. On average, they will travel 6-9 km over the span of a night. In Saudi Arabia, resting sites consisted of dirt overhangs and the base of mature shrubs, in dry river valleys (wadis) and drainage areas.

Predation

Potential Arabian Caracal prey – Arabian Partridges (Alectoris melanocephala) in forest, Hawf Protected Area, Yemen – notice it is the same location as the Caracal shot above.

The Arabian Caracal primarily feeds on rodents and birds, but will also take small desert gazelles, hares, hyraxes, reptiles, and invertebrates. Though quite a capable climber, it hunts mostly on the ground. It will approach its prey in a slow stalk, after which it pounces on its prey. When hunting birds, it has the ability to jump up to two meters in the air, to swat its prey out of the sky.

Livestock, in the form of chickens, goats, and sheep, are sometimes preyed upon. In non-protected areas, these can make up a significant part of its diet.

It will also scavenge readily — in Saudi Arabia, it was observed to scavenge on dead Camels and Gazelles.

When no water is available, the Caracal can get the water it needs from its prey.

Social Organization

Due to the arid climate, which supports less prey, the home range size of the Arabian Caracal is much larger than that of the other Caracal subspecies. One male in Saudi Arabia had a home range size of 270 km² in winter and spring, which increased to 448 km² by the end of summer (it even eventually increased to 1116 km²). In an Israeli study, the home ranges of male Arabian Caracals averaged 220.6 km². This is a large difference when compared to the wetter environments of South Africa, where the home ranges of males averaged 26.9 km². Additionally, the Arabian Caracal has not been found to use a core area (an area most time is spent), unlike the subspecies in Africa. This may be due to the lack of prey densities.

Although unknown specifically for the Arabian Caracal, males territories are probably larger than female territories (as is the case for the other subspecies) and will encompass multiple females for one male.

The young will leave their natal home range at around 9-10 months.

Communication

The Arabian Caracal has a multitude of vocalizations including growls, spits, hisses, barks, and meows. To communicate without direct contact, they will scent mark, deposit feces, and spray urine as part of territorial marking and to denote mating prowess. Smells can be picked up over larger distances through the vomeronasal organ.

Reproduction and Development

Age at Sexual Maturity: males – 12.5-15 months; females – 14-16 months

Birth Season: unknown, but most likely in the spring

Estrus: 5-6 days

Estrus Cycle: 14 days

Litter Size: unknown in the wild, in captivity they give birth to 1-3 kittens

Gestation: 78-80 days

Longevity: unknown in the wild, in captivity they have lived up to 19 years

Population Status

Though the species as a whole is common through much of its range (the IUCN classifies it as Least Concern), the populations which the Arabian Caracal comprises are the rarest. Population counts have not been completed or estimated in recent times, but even old estimates in Pakistan and Iran, labeled the subspecies as being rare. The overall population trend is unknown, but Jordon reported a declining trend.

Main Threats

Hunting is the major threat to this feline. As some individuals predate on livestock, many farmers will kill any Caracal they see on site.

Overgrazing caused by livestock, like this camel, leads to less vegetation, which leads to less food for native herbivores, and therefor a decrease in the native prey of the Arabian Caracals.

Habitat destruction through agriculture, overgrazing, and desertification is the second biggest threat to the survival of the Arabian Caracal.

Conservation

Hunting of the Arabian Caracal is prohibited in Afghanistan, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Pakistan, Syria, Turkey, and Turkmenistan. From my personal observations in Yemen, where truth be told no hunting restrictions exist, it would not have mattered if they had. If a local would have seen one of the animals, he would have most likely tried to shoot it since they were perceived to be a threat to their livestock.

The subspecies is categorized as Appendix I by CITES, which means they are considered to be threatened with extinction and are subsequently prohibited from the international trade in specimens of this subspecies.

A positive for the subspecies is that due to its adaptability it is able to recolonize areas after eradication. It can live in human areas, if there is no direct persecution. With better protection of livestock, this species can survive well even in areas inhabited by people.

Captive Status

There are about twenty five Arabian Caracals in captivity today (or to be more accurate, this number represents the animals officially registered as being captive and does not take into account any illegally held individuals). Most of these animals are in the middle east, with the exception of Moscow Zoological Park, Russia and Melbourne Zoo in Australia which both have an adult male in their collections. The average life span for an Arabian Caracal in captivity is 4.4 years (range 1 day to 19 years).

An interesting fact to me was that out of the 45 deaths that have been noted historically, 9 were caused by injuries from an exhibit mate, five of those from animals less than four months old. Why are kittens killing each other, and is this limited to the captive population?

Traditionally, Arabian Caracals were tamed by people in India and Iran to be used for hunting and for sport in which they had two Caracals compete to see which could kill more birds in a flock of pigeons.

Bibliography

Avenant, N. L. and Nel, J. A. J. 1998. Home-range use, activity, and density of caracal in relation to prey density. African Journal of Ecology 36: 347-359.

Avenant, N. L. and Nel, J. A. J. 2002. Among habitat variation in prey availability and use by caracal Felis caracal. Mammalian Biology 67: 18-33.

Budd, J. 2011. European Regional Studbook for the Asiatic Caracal. Report: 1-46. Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, Breeding Centre for Endangered Arabian Wildlife.

Bunaian, F., Hatough, A., Ababaneh, D., Mashaqbeh, S., Yousef, M., and Amr, Z. (2014). The carnivores of the northeastern Badia, Jordan. Turkish Journal of Zoology 25: 19-25.

Divyabhanusinh. 1995. The end of a trail – The cheetah in India. Banyan Books, New Delhi, India.

Eizirik, E., Johnson, W. E. and O’Brien, S. J. Submitted. Molecular systematics and revised classification of the family Felidae (Mammalia, Carnivora). Journal of Mammalogy.

IUCN. 2008. 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org. (Accessed: 5 October 2008).

Nowell, K. and Jackson, P. 1996. Wild Cats. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

Roberts, T. 1984. Cats in Pakistan. In Jackson, P. (Ed). Proceedings from the Cat Specialist Group meeting in Kanha National Park. p. 151-154.

Stuart, C. and Stuart, T. In press. Caracal caracal. In: J. S. Kingdon and M. Hoffmann (eds), The Mammals of Africa, Academic Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Stuart, C. T. 1982. Aspects of the biology of the caracal (Felis caracal) in the Cape Province, South Africa. M.S. Thesis, University of Natal.

Stuart et al, 1995. Minute to Midnight. Arabian Leopard Trust.

Stuart, C. and Stuart, T. 1996. Report from the United Arab Emirates and Yemen. African-Arabian Wildlife Research Centre.

Sunquist, M. and Sunquist, F. 2002. Wild Cats of the World. University of Chicago Press.

Thalen DCP. 2005. The caracal lynx (Caracal caracal schmitzi) in Iraq. Earlier and new records, habitat and distribution. Bull Nat Hist Res Center 6(1):1-23.

Van Heezik, Y. M. and Seddon, P. J. 1998. Range size and habitat use of an adult male caracal in northern Saudi Arabia. Journal of Arid Environments 40: 109-112.

Weisbein, Y. and Mendelssohn, H. 1990. The biology and ecology of the caracal (Felis caracal) in the Aravah Valley of Israel. Cat News 12: 20-22.

Winger, J. 2005. “Smithsonian Zoogoer” At the Zoo: Caracals, A Black-Eared Mystery. Accessed April 16, 2009 at http://nationalzoo.si.edu/Publications/ZooGoer/2005/6/caracals.cfm